Air Cargo in the Era of COVID-19

The Resilience of Cargo during COVID-19

The unprecedented decline in aircraft passenger volumes around the world as a result of COVID-19 has been well- documented and recovery is anticipated to take longer than past industry shocks (see L&B Lab Weekly, Issue 2, Lessons from the Past and China: How Air Service Might Recover After the Pandemic). The cargo industry, however, is operating closer to its pre-COVID-19 levels than its passenger counterpart. In particular, shipments of medical supplies and high value healthcare consumer goods have been strong enough to keep many freighter schedules relatively intact.

The Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (ANC) in Alaska is an example of an airport that has prospered during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, ANC ranked 2nd in North America and 5th in the world for total annual tonnage, handling over 2.7 million metric tons of cargo. Yet, this was down 2.2% from the preceding year. ANC is heavily used as a transpacific technical stop, as well as a transfer hub for DHL, UPS and FedEx, and for foreign airlines using ANC’s unique air cargo transfer rights.

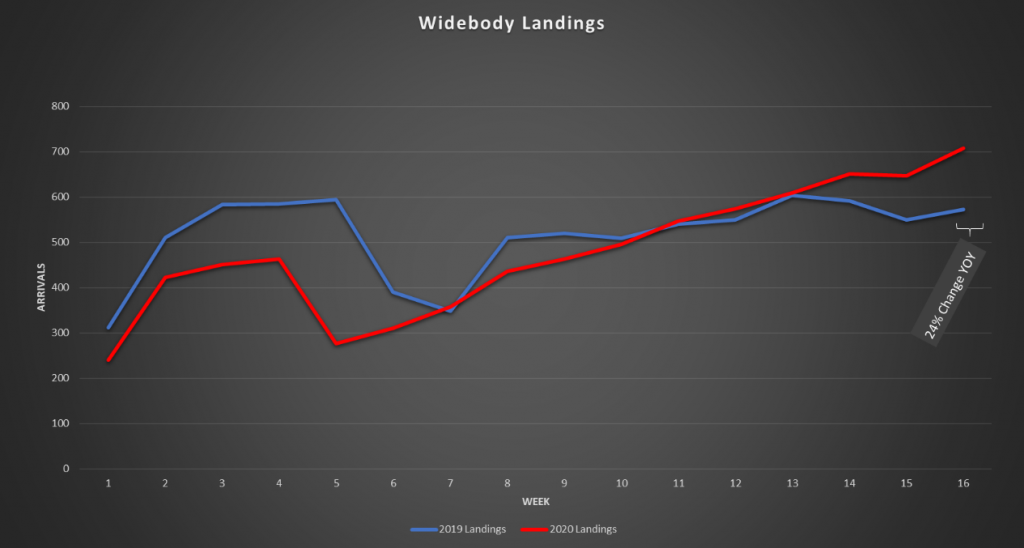

As the exhibit below shows, 2020 started out poorly for number of cargo aircraft arriving at ANC but that started to turn around by mid-February. As of the first full week of May , landings are almost 24% higher than for the same week in 2019.

ANC Widebody Cargo Aircraft Arrivals in 2019 and 2020

Jim Szczesniak, ANC’s Airport Manager, recently observed “we had more aircraft flying to and from ANC than Atlanta did. Forty-one of those aircraft were B747’s, and that was more than all the aircraft to and from JFK and LGA combined, too.”

Third Party Handlers

In recent decades, airlines have increasingly outsourced cargo handling to third party providers who leverage the activity from multiple customers to maximize their use of facilities, labor, and equipment. In doing so, third party handlers greatly enhanced the productivity of airports’ cargo resources.

The efficiency gains of third-party cargo handlers are integral to meeting the demand of existing cargo tenants, particularly at major international gateways. Unfortunately for cargo handling companies, their business models are not designed to survive on cargo-only operations. Rather, they are only able to offer their services profitably when integrated into a comprehensive menu of airport services, including the ground handling of passenger aircraft. While the current efforts of cargo handlers meet the ever-growing demand for goods during the pandemic have become critical to society at large, cargo handlers are operating on the brink of financial collapse and it is important this sector is not forgotten in public support of airports and airlines.

Outsourced cargo handlers have increasingly taken over the operations and leases from airlines. One byproduct is that airport operators are now acting as landlords to third-party cargo handlers, who, in turn, are acting as anchor tenants in many on-airport freight facilities. Looming bankruptcies for third-party cargo handlers could leave airlines without critical support services for both cargo and passenger operations. Additionally, there is no indication that closure of these cargo handlers would open the market to competitors. Therefore, airport operators must be vigilant in investing in these anchor tenants.

Airport Recovery Should Include Investments in Cargo

A significant consolidation of both the dedicated airfreight operators and passenger airlines (and hence belly freight) occurred in the lead up and aftermath of 9/11 in the United States. Consequently, many U.S. airports were left with unprecedentedly low occupancy in cargo facilities. Several major international gateways missed opportunities to redevelop cargo facilities while this rare surplus in cargo capacity existed. By the time Amazon spurred a new growth spurt in demand for on-airport cargo facilities, many land-constrained airports had lost the flexibility to use the surplus of cargo capacity. Conversely, the few airports, like Chicago O’Hare International Airport, that proceeded with facilities improvements during this time were rewarded with competitive advantages when the industry recovered in early 2010.

With the all-cargo carriers already battle-tested in the last twenty years, many of the weaker competitors were eliminated or acquired. At most U.S. airports, FedEx, UPS, and ACMI carriers operating on behalf of Amazon and DHL account for 90% of annual cargo. Changes already underway to accommodate e-commerce growth and life sciences only grew in importance, and airport operators should see little cause to delay development.

Major gateways with mixes of international and domestic passenger and all-cargo flights may observe new rounds of carrier acquisitions and bankruptcies that create temporary vacancies. Airport operators should not miss the opportunity to use this rare surplus capacity for redevelopment projects that are far more challenging when all cargo facilities are fully occupied.

Contributors: Written by Kevin Hoffmann and Mike Webber with LJ Marciano and Gary Gibb